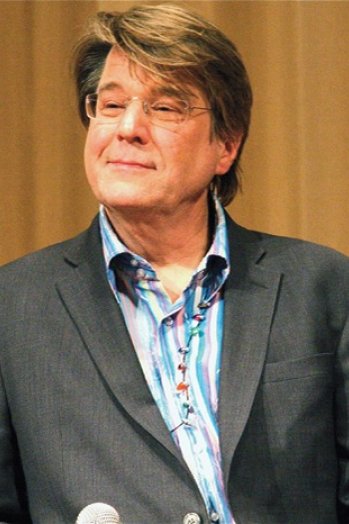

From the first time I heard the music of Christopher Young, I knew that he was a composer that possessed talent and was able to compose innovative and quality music for film. I cannot recall whether or not I added HELLRAISER or DEF-CON 4 to my collection first, but both of these scores had a lasting effect upon me and it was because of these two powerful soundtracks that I continued to look out for the music of this gifted composer. He quickly gained recognition from both critics and fans and is still today one of the most admired and collected film music composers. I still nearly 33 years later get goosebumps when I hear his sweeping and commanding theme for HELLRAISER and I am still in awe of his intricate and melodious musical passages for the movie HAUNTED SUMMER. He is himself an icon of film music and a composer that has broken new ground with each score he writes. jm

I have fond memories of discovering your music for the first time, my first album was DEF CON 4 on Citadel I think, I always remember you scoring even low budget movies with big orchestral soundtracks, was this something you did right from the start of your career?

Absolutely. I got the reputation of being someone who could record a score for less money than anyone else, or at least for a very low budget. I used the connections that I had made as a student at UCLA to put together a very affordable package for the production companies. My mission was to try and provide a score that outdid the production value of the film. The composer can never be criticized for the failings of a movie, only the music, so I tried my best to lift the movie and to make it shine. Remember, this is in the pre home studio synth mock up days, so even the lowest budget movies had to come up with the money to hire live musicians. The record actually was not on Citadel, it was on Cerberus records, which was owned by Richard Jones. He is a fantastic guy and I was so lucky that he was willing to release my earliest work.

When I was doing the early New World Pictures movies, one of my tasks was to try and create a main title that would falsely illustrate what they were hoping the movie would be. It was like I was trying to convince the audience that they were about to watch the greatest action, horror or sci-fi film ever shot, which was the case with Def-con 4. Shortly after the main title however, within 15-20 minutes into the movie, the audience would start to realize that the film was not all that the music set it up to be. The director wanted the music to lift the film up into the stratosphere where it could compete with the big budget movies. The small production companies aspired to do high quality films, but didn’t have the money, so anything that they could get from the composer to make their movies appear to be as big as the legit films by the major studios was encouraged.

What are your first memories of any kind of music and were you from a family background that was musical at all? Perhaps I am too old to remember my first memories of music, but of course it was there from the beginning.

My Mom sang in the church choir, and my Dad, although I love him to death, was tone deaf. We had a Victrola and a collection of records; however I do not remember my parents ever pulling one out and playing it. The music in the household was from the AM radio, tuned to the stations that played The Beatles and the rock music of the 1960’s. My Mom would listen to WNEW from New York City. The DJ’s name was William B. Williams and he would play big band vocal music featuring artists like Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin. My brothers and I all played drums, and three of us always loved music, but lord knows where it came from. We were addicted to it from the beginning. My older brother still works in the music industry as a concert promoter in Florida, and my younger brother is an enthusiast. He listens to music constantly. Mostly 60’s rock. There was no musicianship from anyone else in my family, so I was sort of a freak of nature. My Dad, and his Dad, and his Dad, were all lawyers, so he was hoping that one of us would become a lawyer, but that never happened. I do remember the first moment that I was encouraged to do music, as it was never something that my family looked favorably upon. They couldn’t argue with me going to the Presbyterian church on Sunday, and singing in the choir, which was believe it or not a slightly paid gig at the time. I’m so thrilled that I had that experience because there is nothing quite like immersing yourself in three- or four-part vocal music. It was a mixed men’s and boys’ choir, and we would sing the English hymns and anthems. Just remarkable music.

I had two choir masters, both of whom were fantastic. The second one, Craig Smith, is a wonderful organist as well, and I also took lessons with him in composition. I have memories of going to church on Sunday to sing this wonderful music, as well as on Easter and Christmas eve, doing the special services and knowing that I can actually do this and not feel bad about it. To not feel bad about singing and feeling comfortable in my own skin and being able to be at that moment completely immersed in music.

My family was never thrilled about me pursuing music professionally. I think they realized in my senior year of college when I majored in it, that there was really no going back, but they still weren’t thrilled about it. My Dad was the practical one who said, “well listen, if you pursue music, you’d better get a teaching certificate.” He was all for me doing what I needed to do so that I could teach. Incase making music didn’t work out. I wasn’t so into that idea and I think that disappointed him, or at least worried him. I remember the turning point was when I returned home after finishing college. I had fallen in love with film music but wasn’t ready pursue it professionally because I hadn’t attended a conservatory that developed the kind of tools that were required of someone who wanted to be a film composer at that time. You had to be able to write for instruments and orchestras, and if you didn’t know how to write a tune you weren’t going to have a career. You also had to be able to write in a variety of styles. I had the music in my head, but I just didn’t know how to get it out, so I moved to New York City and took night classes at Manhattan School of Music and Julliard while working at a delicatessen around the corner during the day. I did that for a year and then reapplied to music schools because I knew I had to go back and really start learning. When I applied to study at Julliard and Manhattan School of Music, I was rejected. I was also rejected by UCLA and USC. The only school I was accepted into was North Texas University in Denton, Texas which is a fantastic music school. I remember I had the letters of admission sent to my parents house because the address I had in NYC was such a dump that I don’t think the mailman would have even wanted to go there! I went home one weekend because Mom said I had received some letters from the schools I had applied to. I remember opening one when she was by my side which said I’d been rejected, and I started crying in front of her. Balling like a baby. I think at that moment she realized I was serious. That this was for real. I remember she said the nicest thing to me. She said, “screw them, they made a mistake”. It was then that I realized we were a team on this one. That really was the breakthrough moment. I think the reason I got accepted is because one of my teaches at Hampshire college had graduated from that school. He was living in NYC and helped prepare me for the entrance examination. I also think he made a call and said, “I don’t know how this guy is going to do on this entrance exam, but I think he’s got some talent, please accept him”. Low and behold I did get accepted and I was just over the moon. I studied at North Texas for a year and knew I was going to accumulate the credits that I’d missed as an undergraduate. Interestingly I knew someone at UCLA who was on the music faculty, Older Nashforth? He ran the electronic music program there and happened to be the half-brother of my Moms best friend. He helped navigate that. He said “Ok. You want to get into this school? You are going to need to do these six things.” So, I applied myself to those things, reapplied the following year and got in. So, I did get accepted into UCLA, never USC though. They never accepted me. It’s interesting because now I teach there.

One of your recent scores is for the new version of PET SEMATARY, your score is great, the use of symphonic, electronic and voices is totally absorbing, how long did you have to work on the movie and where did you record the score?

I was on Pet Sematary for an extremely long period of time. Longer than I’ve been on any movie that I can recall. It was five months, and by the time I’d finished the album release, which is still yet to come out, nearly six months. Truly an extraordinary amount of time. I’m thrilled that I had the opportunity to spend so much time on the music, because the score certainly evolved over that time period. It went from what was originally an orchestral score, to an electronic score. I’m honored that you think I used a symphony, because there was actually no recording done with an orchestra. Live instruments were recorded at my studio, sampled and then mutated. There are moments that sound orchestral, but they are sounds that I created from my previous recordings. I am thrilled to hear that I fooled you and others in some cues. That was my intent. To make it sound like an orchestral score, without having to go down that route.

HELLRAISER was the breakthrough score for you, how did you become involved on that movie and what size orchestra did you have for the score and did Clive Barker have any specific ideas as to what style or sound he wanted for the picture?

I got involved in Hellraiser because by the time it was in production, I’d already become the in-house composer for New World Pictures. As I mentioned in the first question, they were in the business of taking extremely low budgets and coming up with films that could compete with the major studio pictures. You also mentioned Defcon 4, that was a New World Pictures pick up film. A film that they bought from a company in Canada that was going out of business. I’d done a bunch of these movies for them. The then head of post-production, Tony Randall, who ultimately ended up directing the sequel, Hellbound, was sent over as a representative of New World Pictures to London. Everything was being shot there because Clive Barker is from England and the cast were all English, excluding a few people such as Ashley Laurence who flew out from LA. Tony Randall was a fan of mine by then and recommended me to Clive. Clive was planning on using an industrial band from England called Coiled who make remarkable music, but I think Tony brought to his attention that they hadn’t done a movie score before, and that they weren’t going to be able to do the things that a horror film required. You had to be cut specific in horror films. You couldn’t just lay down an ambient track, or at least you couldn’t back then. You had to make the music align perfectly with specific cuts. I mean, can you imagine if something violent is happening on the screen but the violent stroke in the music is a second late? It turns a horror film into a comedy! I think Tony sold me as being someone who would be able to time the music perfectly. I remember Clive saying to me at a hotel near central park in New York City, “I don’t want that Nightmare on Elm Street sound. This is a sick romance and this score needs to acknowledge that.” The score needed to sell the love that Julia has for Frank, even though it’s a sick love.

The music needed to make the audience sympathetic towards her and help them understand why she goes out and kills people to bring him back to life. Clive said, “You’ve got to keep in mind that this is a twisted, sick, unhealthy romance, dark and tragic and not just a screamer, not just a slasher, not like Nightmare.” That was his primary guidance.

We didn’t have a full-size orchestra because it was a low budget movie. I wrote for a string section, two pianos, two harps (panned hard left and right), four French horns, which I expanded upon for Hellbound to eight French horns, low brass, as well as flutes and bassoons. No oboes, clarinets or trumpets. I also used a pretty big percussion section. I did some pre-records for a few action cues too. For the most part it was a string heavy score. I remember thinking that the score was going to be too big for this small film because it takes place in a claustrophobic house, but it was Clive that talked me into using an orchestra. It’s interesting that the most famous cue in that movie has just come up again. That being the resurrection waltz, when Frank comes back to life. I always thought it was Clive who suggested that we do a waltz, but I read an interview recently where he credited me for coming up with that idea. I’m afraid I can’t remember, but I must say that doing a waltz during that scene was the right idea because it is not the expected thing to do. It was a turn of a resurrection, this evil scene, into a ballet, a gothic ballet, and made something that could have been a screamer into something sickly pretty.

There was an article in SOUNDTRACK magazine a few years back and you were recording with THE GRAUNKE symphony orchestra, do you have any preferences when it comes to where you record, and do you have a line-up of musicians that you turn to for creating certain sounds etc?

Back in the early days, when I did my first set of overseas scores, Hellbound being the first one, I went to Munich, Germany, and recorded at the Bavarian music studio with the Graunke symphony orchestra. I did several movies with them but then moved on. I spent a fair amount of time in London and did a lot of recording at Abbey Road, CTS and Ayer Lyndhurst. I’ve tried pretty much everywhere but nowadays the orchestra I love working with is the Bratislava orchestra, which is run by my great friend Paul Talkington, who I met for the first time on Hellbound. I’ve been using the same fixer since then. They call them fixers in Europe, and contractors in LA. If I get a film and it must go overseas, the first person I call is Paul. I have a great thing going with the Bratislava orchestra. They seem to understand my music. I don’t speak their language, so we have to communicate through a translator. They put 120% into it and I’m thrilled with the recordings I get there. The other places in the USA of course the local orchestras are fantastic you can’t beat them they’re awesome. I’ve recorded in Seattle, Salt Lake City, and New Orleans as well.

If there are some special things that I need to accomplish, you know, some acoustic instruments that are specialty instruments, you really can’t get those overseas unless they are instruments that the natives play as part of their folk music environment. The music that is intrinsic to their culture. You don’t go to Ireland to have someone play the sitar or duduk. Those instruments can be pre-recorded here. There are a handful of musicians that I use depending on what it is that I’m looking. That is the wonderful thing about LA. People from all over the world come to live here and they bring their instruments with them!

What musical education did you have, and what areas of music did you concentrate upon, and was film music something that you had always had in mind to focus upon?

When I started studying music it was with the intent of becoming a professional drummer. When I was a kid, I and wanted to be the next Ringo Starr, and when I discovered jazz, I wanted to be the next Buddy Rich. I was pissed off at God for not making me either of those players. I studied at Berklee College of Music with a great drummer by the name Alan Dawson, David Brubeck’s second drummer. He didn’t think I was very good, and it broke my heart. I had started to get into arranging and writing a little bit. I didn’t know what I was doing but had started to hear things in my head and wanted to learn how to capture those ideas. I discovered film music when I was 18. It was by chance when I purchased the album entitled “The Fantasy Film World of Bernard Hermann” which had suites of his music that he had prepared and had conducted in London as a re-recorded album. It was released on Phase 4 records and had suites from films like Journey to the Center of the Earth, 7th Voyage of Sinbad, The Day the Earth Stood Still, and Fahrenheit 451. I remember dropping the needle on that record, and within the first four seconds seeing the light. I wasn’t a big fan of films but had fallen in love with the music. In those days you had to go to the theatre to see movies, and I was too busy playing music. I knew the songs from the James Bond movies, but not the score. This Bernard Hermann record changed everything. My own writing, or whatever little writing I’d done was always seeking out that which was mysterious, that which reflected the invisible world somehow. Not scary music, but something mysterious. That record changed my life really in a matter of second. I’d become obsessed with wanting to know more about Bernard Hermann. Again, you couldn’t rent videos out and there were two ways you could see these movies. Revival houses in NYC, or a show called the Million Dollar Movie on channel seven. They would show the same movie every single night for a week, so I would record the audio using reel to reel tape, and then listen to just dialogue and the music the following day. I would then watch the film the following night to see how the music was playing under the dialogue. Records were hard to find, and you couldn’t rent the videos. There were no books on film music except for Tony Thomas’s Music for the Movies. That was the only book on film music that I couldn’t find without having to search hard. I knew those cues and I was waiting for them to happen. That’s how I learnt how to do it. I would also go into movie theatres and record the film audio with a portable cassette machine and listen back to that.

There was no musical education in Grammar school back then, so the only musical education that I got was, as I said, going to church every Sunday and listening to the popular music on the radio. Early rock’n’roll and vocal big band music. Songs was all we had in the house. Instrumental music was something I’d never heard. I thought Beethoven, Bach and Brahms were irrelevant to music. I didn’t know there were still composers who were writing music for the orchestra. I thought Beethoven had evolved into The Beatles. It wasn’t until I went to college that I got an education. I went to a prep school called The Gunnery in Washington, Connecticut, to do an independent project which was studying jazz music. There may have been one class on music, but it wasn’t until I went to college where they had two faculty members who were composers that I could start to think about studying music. It was such a liberal school; it gave me the freedom to do whatever I wanted to do. It all worked out fine, but I certainly wish I had been thrown into a situation where I was required to take the classes that someone at a conservatory had to take. Harmony, counterpoint, ear training, orchestration etc. I would say it wasn’t until I went to North Texas that I really started getting it together. And then, after that, at UCLA. It was about a three-year period where I was completely focused in on studying scores and listening to all types of orchestra music.

I was getting as far away from pop music as I could. During that time, I started listening to modern classical music and it was the best thing I could have ever done.

It’s surprising that HELLRAISER was 30 years old two years back, the score was re-issued in an expanded edition, would this be something that you would like to see with any of your other scores and were you involved in the compiling of the 30th anniversary release for HELLRAISER, in fact do you like to be involved with any releases of your scores by record labels?

Yes. Absolutely. I am anal retentive about wanting the record or CD releases of my scores to be the best they can be. Indeed, I was involved with the reissuing of Hellraiser. I had the time, and they had the money to allow me to remix it. We duplicated the format of the original record and they added some additional cues. I’m not a big fan of that. The composer knows the score better than anyone else and if they care about what they’ve done they want to filter through and get rid of the dead weight material so they can work with the best of the score and structure it into a meaningful listening experience. I try to figure out ways of sequencing the cues, editing between them, and writing additional material to make the cues flow more naturally into the next. I completely try to govern every element. The overall levels of each cue, even the space between them, let alone the sequencing. When I first got into film scoring, vinyl was the way that music was made available to the general public and you were only able to put a certain number of minutes on either side. They expanded over the years and you got to the point where you could put 23 minutes on either side, but usually, it was 18 minutes each side. There was something wonderful about that because you had to structure the music knowing that at the end of side one, they would have to flip the record. Knowing that you had to structure the music to keep the listener entertained. I used to think of records, I still do, as doing your song and dance on stage. You have to start with a bang, then end with a bang. For me the best records kick off with a bang, using the main title, then end with a bang which is using the end credit. Sometimes you use a song for the end credits. I used to love the way Goldsmith used to put his records together. He was my role model. He would start off with the main title and then go into a series of subsidiary themes. The love theme, for example, would often be the second track. Sometimes he would join all the thematical material in the first couple of tracks, and by the third or fourth track would start the variations of these themes. It was always paced very well. How many slow cues can you have before it’s time to have a fast cue? The end of side one would go out with a bang. He didn’t trickle out on side one. If you go out with a bang it was like ok, what’s next? Sometimes if there was a song that was written by a composer that was written for the movie it would start side two. It would either be the first track on side two or the second track on side two. The second track on side two would usually be the score and an action cue. The penultimate track on side two was usually the grand finale. The final big cue for the final moment of the movie. That was the guiding light, and that was how I liked scores to be presented. Which means you have to know when to get off the stage. The problem with CD’s is that there is no side one or side two, and generally speaking the record labels want to stuff them with as much stuff as possible. A lot of record labels would put every single cue from the movie in sequence. Fans liked it, but who the hell could get through it if you were not a fan? Once I was given a CD from a film which had 24 tracks on it! I thought it was a terrible mistake.

Try to join them or do something, but don’t put them in the order of the movie. It doesn’t work. My big project now is reworking my old scores into a more satisfying musical listening than even the way they were released on CD or record. With CD’s or records you are taking cues and are offering them up in the same kind of format as a rock record. Each track is three or four minutes long, like vocal songs. I am turning them into tone poems or suites, where there is more time spent on a track. It’s just one continuous piece that lasts for up to sixteen minutes and represents the entire score.

I think I am right when I say you do not conduct, is this because you prefer to supervise from the recording booth, so that you can ensure the music sounds as you want it too?

It’s for two reasons. When I started off doing my student films at UCLA there was so little money that the students would come in during a class break and be willing to stick around for a very short period of time if they were paid in pizza and twenty-dollar bills. I knew that going out on stage, and then running back in to hear playback would eat up time, so I got into the habit of having someone out there while I could stay in the booth and immediately know what was happening with the music and be able to make changes. I would find good conductors who understood my writing, and so I never felt like they were failing to get something out of the music that only I could get out of it. The best conductors that I’ve worked with, like Alan Wilson, understands my music better than I do in a lot of ways. He knows exactly what he needs to do to get the music alive. Number two, I think I’d be a terrible conductor because my head would be in so many places at the same time. I am acting as the producer of the score and we are always having to worry about how much time we are spending on each cue. Thinking about what is coming up and what went wrong before. Can you believe I’ve never stood in front of an orchestra and conducted my own stuff, let alone anyone else’s stuff? I’ve never seen myself doing it.

The track RESSURECTION, from HELLRAISER is so powerful, it’s like a grand sweeping and macabre waltz, can you remember the instrumental line up for the cue?

That is the one we were talking about earlier. The resurrection scene of Frank. Again, I can remember that to a certain degree. It is the same orchestra we had for the rest of the score. We had two pianos, the four French horns, low brass trombones, bass trombones, full string sections, two harps and lots of percussion. I double tracked the strings to make this cue a bigger. There were two versions of this cue. As a matter of fact, I had to redo this score. The original was my favorite which had the theme played on two pianos. Both playing the melody panned hard left and right. I just loved spreading the pianos and having this big powerhouse keyboard sound. As I recall, Clive didn’t like the pianos and wanted the bassoons playing the melody. This is the version that made it into the movie. The one that was originally recorded, which is also on the album, with the pianos. Resurrection is the one that has the pianos, and re-resurrection is the one that ended up in the movie.

It is basically the same orchestra with the second piano. Like I said, I think I may have double tracked it. Doubled the strings, doubled the French horns, doubled the brass. That’s what we would do back in those days to make a score sound bigger. Double it. Play the same parts a second time.

You scored JENNIFER 8, your score replaced one that had been written by Maurice Jarre, when you went to see the movie for the first time was Jarre’s score still on the movie, or had the director removed it and installed a temp track?

Bruce Robinson was kind enough to show me the film without Maurice Jarre’s music. As a matter of fact, I’ve never heard what Maurice Jarre did for that movie, even though there is a CD which has his score and my score on it. Still to this day I’ve never listened to his stuff. I have the utmost confidence that because of the immense talent, brilliance of Maurice Jarre’s music, that what he did was special and probably would have worked if it had been a different director, but Bruce had a vision of what the score should be and I don’t think he and Maurice were seeing eye to eye on it. I was Bruce’s first choice, but the studio didn’t think I had enough meaningful credits to be able to score a major studio movie, so when Maurice’s score was thrown out, Bruce got the right to bring me on board. It was a last-minute thing and I remember I was scared shitless. I knew this was truth or consequences time. It was my first big studio movie and if I fumbled the ball on this, my career was over. I was nervous. With great fortune, Bruce directed me in such a way that I gave him the exact score he seemed to think he needed for that movie, but it didn’t come quickly. I remember my first attempt at a main title was a total misfire. I brought it to Warner’s Hollywood, and I thought I was just going to meet Bruce. They were working on the dub stage and stopped to put my cassette into the audio player. There was dead silence and I knew I’d fucked it. I was fucked. Finished! Bruce pulled me aside and sweetly told me that I’d missed it. He said the right things though because on my drive home at the intersection of Wilshire and Santa Monica Blvd I got this idea. I sung it into my cassette recorder, went back to my tiny little dumpy apartment and worked it out. I called Bruce up and played it to him over the phone. He said, “that’s the theme, that’s my movie!”. I took what was a disastrous show and tell and turned it into something positive.

Staying with temp tracks, do you find these to be distracting or constructive?

Well, I’m not going to lie, I find temp tracks to be terribly destructive. I divide all my scores into two categories, the ones that are and the ones that might have been. What do I mean by that? The scores that I’m most excited about, often, not always, are the movies where there is no temp. Or there was temp, but it was bad, and the director even said we’re at a loss, we don’t know what to do with this movie, please save this. Do what you think is right, not what is in the temp. Those usually give you the opportunity to do something substantial. Like on Jennifer 8 there was no temp, so whatever I did had to come out of my edits. It’s very nerve-wracking because you truly must come up with something from nothing. The ones that have temp, which nowadays almost all of them do, invariably influence your thinking. It’s impossible to shake it off. The composers’ brain is like musical fly paper.

You can spend a lot of time trying to remove it so you can make space for your own thoughts. Directors and anyone else who works in movies can’t quite understand the kind of effect that a temp score could have on a composer because there is nothing quite like it. It’s not like when a director takes on a movie the studio sits down with them and shows them a movie of clips from six or seven movies that they want the movie to look like. They can talk in the abstract by saying “we wish this film had the effect that Alien had on the audience”, a sci fi thriller as an example, but they don’t put together clips from other movies, and that’s what a temp score is. It’s easy to take music from other movies, chop them up and throw them up against picture. I always ask myself the questions “what might have been if there was no temp in this movie? What might I have done if I had never heard the temp?” Bernard Hermann would storm out of the theatre if temp music was played, and Elmer Bernstein just wouldn’t attend a screening if it had temp. That was back in the days when composers were encouraged to come up with something special for the movie. Now, there is this issue with not veering too far from the path. That’s why so many scores have to sound like redoes of a redo of a redo of something that might have been original twelve years ago. It’s killing film music because if you’re being asked to stay on path with the temp, you are going to sound like a second-rate version of the temp. I understand why directors like to present to the studio their movies, because a lot of studio execs don’t feel as though it’s working without music. It eases the director’s ability to talk about something that they know nothing about. Directors can study film making, script development, casting, editing, lighting, camera technique, costume design, location, but when it comes to music, very rarely have they had any formal training. They use temp to try to find a common ground, so they don’t have to say much. I just wish that at the beginning they would eliminate the temp so the composer could wander around blindly and find the score on their own.

I make no attempt to hide that I love your score for HAUNTED SUMMER, there are so many beautiful themes in the score, you got the balance just right fusing synthetic with symphonic, what percentage of the score was performed by synthetic instrumentation?

This film goes back a bit and it has been a long time since I’ve listened to it. Again, I can say with certainty there was no orchestra used in that score however there were individual instruments brought in which were used to enhance what was otherwise an electronic score. Those instruments being a string quartet a piano a harp I think a solo alto flute, the alphorn, which is a long white pipe used in Switzerland, a folk instrument used to communicate between alpine communities. I remember finding the only alphorn player in town, In essence it’s a chamber group. A small group of acoustic instruments in conjunction with pre-recorded electronics. I am thrilled that you like that score. It was really the first legitimate drama that I had been asked to score. It was a big moment for me because up until that moment in time it was as though I had already been type cast as the spooky movie guy, not intimate dramas. It was a canon movie and they just didn’t have any money to get big name composers. I remember doing a demo for that director Ivan Passer, the Czechoslovakian director, and Eric Stults the actor was in that movie. He got involved with postproduction because he wanted to get into directing at the time and also selected my demo and he said I think he’s the right guy for this movie.

I didn’t see the movie; it was just based on them telling me about what the movie was about, and I don’t think I ever saw the movie as far I can remember as in spotting it. All I remember is this demo got me the job. I was absolutely thrilled to be on that movie. I remember we all thought it was going to take off. It was Cannons last film before they went out of business, so it never went anywhere. It was based on the lives of Mary Shelly who wrote Frankenstein and Percy Shelly the poet, Lord Byron the poet and John Poledory, also a poet/writer and Claire who was Mary Shelly’s cousin and the weekend they spent together on the lake in Switzerland on where they challenged each other to write a scary story. It was that weekend that Mary Shelly came up with the idea for Frankenstein. I love the film. It was gorgeous. Well-acted, I thought this was the drama that was going to make me a serious contender for dramas. I don’t think it was ever released in cinemas. Really sad but I appreciate you feeling that way about this score. It was definitely a diversion. I’ve never done anything quite like it or worked on anything like it since.

You scored SWORDFISH, there was also music on the soundtrack by DJ Paul Oakenfold, did you collaborate with him on the score or did you work separately?

You know he was on board before I was on board. We had talked about doing some collaborating. He was a very successful DJ and was doing lots of gigs at that time. I remember being invited to go to one of his raves downtown to check them out and I couldn’t believe how loud the music was. I remember I had to wear earplugs on earplugs just to get through that evening. But as it turns out he had to go on the road to perform, and we never did sit down and look at the movie together. I remember through his assistant; some loops were delivered to me. That is as close as we got. Loops and drum patterns. I remember meeting with Joel Silver who was the producer on that movie, he did the Lethal Weapon movies, he turned to me and said take what you can out of these loops but make it a great orchestra score. It was a very short postproduction. It was very rushed. In the end his assistant helped provide grooves that I used in about two or three or four cues, maybe more than that but for the most part I was on my own. I would not say it was the kind of collaboration I was expecting it to be. He is great and I loved having the opportunity to add orchestra to his loops. I was hoping it was going to open the door to me collaborating with other people from the pop world. I would love to have done more of that, and I would still love to do it.

The only other time I was given material by someone from the pop world, was when I had to incorporate some Peter Gabriel music into a score. I had to do arrangements of a theme of his for a film called Virtuosity. I had to include a theme of a song of his for a movie, so I did orchestral arrangements of that tune. Then I had to incorporate some of his loops into the score. We did finally meet, but not when I was working on it. As I recall now, that is the only two times I can remember when I could interact with someone who was established in the pop world.

What is your opinion of the lack of Main title themes in movies in recent years, there was always the opening theme or end theme for a picture, but they seem to have disappeared?

Themes are something of the past. It’s unfortunate but true. I think everyone is afraid. Directors and studio executives. I think they are afraid that they represent a past which could do damage to their movies. They say too much and they’re afraid it may come as a dated, corny additive. It’s unfortunate because historically great tunes combined with a great movie make great bed partners. There is nothing more rewarding than to have some famous tune bring to mind a movie. You hear the Tara theme from Gone With The Wind and you immediately think of that film. It’s the same for Star Wars. When you moved out to Los Angeles, as I mentioned earlier, you had to know how to support a dramatic situation properly with music. You had to be able to write a catchy tune, and you had to be able to write for an orchestra. You had to do both on your own and hear it in your head. You also had to know how to vary those tunes, as the best scores were comprised of themes and variations. You also had to be able to write in many styles. Indeed, the absence of themes is the biproduct of the home studio synth sample library created scores. A good tune requires a somewhat rich harmonic backing. Synth scores are really not the best at doing really richly developed chordal scores. They hover around a pedal in which the chords, usually used a minor based triad that do not move too far away from that tonic drone and there is only so much you can do melodically on top of something that is not going anywhere harmonically. Synths have kind of killed melodic writing. There are certain things they can do well, and certain things they don’t do well. Synths are not great with moving around with the same kind of harmonic ease that an orchestra can.

They prefer to push a note down on the keyboard and let it sustain for a long period of time, pads and ambiences where pitches mean nothing. So much of the ambiences now are about the production and the pitches are almost irrelevant. As a non-thematic score what relevance should they have? The one thing about the great scores of the past is that themes were established at the onset of the movie and that was the driving material that tied everything together. Even if the composer was not doing it consciously it was inevitable that somehow, some aspect of those themes would influence the shapes and the ideas that came to them as they were working on each scene. If you don’t have a strong tune you cannot have a strong score. There are instances of non-thematic scores which are held together really well, but as a general rule, strong scores are held together first and foremost by one or more strong themes. In the short history of film making and film music, composers are generally known for their hit themes. The right theme for the right movie. When the general public think of John Williams they think of the themes of Jaws, ET, Star Wars, Indiana Jones, themes you immediately recognize are from those movies. They are very well written tunes. Elmer Bernstein had The Magnificent 7, Lalo Schifrin had Mission Impossible, Jerry Goldsmith had Star Trek, Alfred Newman had the 20th century Fox logo music, everyone had their theme, Dimitri Tiomkin the green leaves of summer from the Alamo. The list goes on.

Staying with current trends within film scoring, what are your views on the DRONE sound that is being utilized by certain composers, is it music or is it just a sound that runs under a scene and fills time in a way?

Yes. To continue with what I just said, the drone scores have absolutely taken over film scoring and little did anyone know in the 80’s when they started easing their way into the language of film music that as of today they would have completely taken it over. I remember that in the 80’s that Tangerine Dream and Giorgio Moroder and Vangelis and Jan Hammer were the first composers to introduce this idea of this static drone going on and things happening on top of it. You know I’ve always said about drone music that if you’ve got a drone going your chained to it. It’s like a kite being tied to a top of a flagpole that even during a windstorm if its tied to a flag pole they can fly around but it’s never going to leave that flag pole. Drones are like that flagpole. Nothing much can happen you’re kind of stuck it’s like quicksand it takes the life out of harmony and melody so you know I don’t mean to completely annihilate them the public adores them, young composers who were raised on scores like that think they’re the greatest so what do I know I’m just simply saying that for sure drones have killed really the harmonic and melodic complexity that used to be so much of film music up until and through the beginning of the 80’s. Its inception until the middle of the 80’s. Inception is the first film that had its score written for it in its’ entirety King Kong 1932. Remembering that the first film score was written by Camille Saint-Saëns the French composer in 1902. Film scores have been over around for over a hundred years but not much more. Film scoring didn’t really kick into gear until the 1930’s after King Kong I always find it interesting that the very first film to have a score that worked in a totally inclusive way music from beginning to end underscoring a scene in the way we understand underscoring now was for a horror movie because they realized that without it, it wouldn’t have been a very successful horror film. I remember the guy that produced it Miriam C Cooper was in a state of panic because he had this giant monkey running around and everyone is going to think it’s funny. It could backfire because this giant monkey out on an island that gets taken to NYC could kind of backfire and find it funny. He turned to the composer Max Steiner and said save this movie. He said I’ll have to out music from beginning to end and score it like an opera. At the time the general consensus was we can’t have music in a picture unless we can actually see the musicians playing on scene. We see people singing ok you can have the orchestra accompanying it. But if there is no one seeing and music is heard we need to see the band playing, you can have music at the Main Title and the End title but no underscore, it just wasn’t heard of. There was one movie that had a lot of underscore that max Steiner did just before King Kong. I can’t remember the name of it now, but King Kong was the big game changer. Because Max said to him, we need to have underscore. The audience may think it’s kind of weird and were afraid that the audience wouldn’t be able to embrace what is happening unless they see the orchestra while the drama is going on. They had to do it in King Kong to make it scary and people embraced it. I miss those days. I can’t tell you how much I wish time would turn back and I’d still be in an environment when I was totally encouraged to write themes. I like doing things that are not thematic especially in horror movies but there is a time and place for that but for the most part themes are it and will always be it and they will return. They will come back to Hollywood one day victoriously.

What composers, film music or classical would you say inspired you or influenced you?

I would say when I was a kid in the world of pop music the three B’s. The Beach boys, The Byrds and The Beatles were probably the greatest influence on me. The three B’s in classical music however Brahms, Beethoven and Bach, I never paid much attention to them. The three B’s of Pop I do. All that pop music and the British invasion and everything in the 60’s highly influenced me. My last attachment to pop music was the prog rock movement. I was very influenced by bands like the Procol Harum, The Moody Blues, King Crimson, Emmerson Lake and Palmer, Jethro Tull, and the final band actually was Gentle giant. They were the last band that captured my attention and when they disbanded, I departed from rock music. In the jazz world and anything that any drummer did in a big band or combo situation whose drummer I liked I was attracted to. Compositionally I loved the stan Kenton orchestra. That certainly was the cross over into discovering orchestral music. In the world of orchestra music, non-film music I would say that I am most interested in the contemporary music scene. When I say contemporary, I mean post world war two, orchestral concert music especially American composers.

I have to say realistically the whole Polish school influenced my thinking. Penderecki, Lutosławski, Xenakis, Ligeti, those were the main players. It’s an endless list of people though. In American music Aaron Copland and Roy Harris, John Corigliano, it’s like a massive list. There are so many composers I’ve learnt so many things from, but I keep myself open to that constantly. I have this insatiable need to consume more music. I am always wanting to know more and am never satisfied with what I know. I am always buying CD’s still of music I’ve never heard before and investigating that composers work and take something out of it and see how it might influence my own thinking. In the concert world I am most interested in the contemporary composers. I do not listen to the old composers. Late romantic composers I do like. The polish composers like Tchaikovsky, Shostakovich Prokofiev, Rimsky-Korsakov and the Russian composers. I do like Sibelius’s 4th symphony, it changed my life. There is nothing like listening to a great Charles Ives piece, his 4th symphony. I am just fascinated by all of that and am very glad to have spent so much time in the concert music world because a lot of film composers now I understand the real orchestral music they probably fell in love with was a John Williams score. I used to say with my USC students the first group were the Star Wars generation, then the Indiana Jones generation, then the Jurassic Park generation, then the Harry Potter generation, it’s the next wave and the scores they probably heard in the theatre of their favorite.

I remember the first scores I heard in film music that I thought was remarkable was the Wind and The Lion by Jerry Goldsmith. I am glad that I didn’t stay exclusively with film music. So many film composers only listen to film music. You want be the next John Williams? He didn’t just sit around listening to Korngold all day long and other film composers, he was out studying classical music. His big thing was the English group of composers, Vaughan Williams, Walton and Holst, Howard Hanson, these kinds of late romantic composers and that is why his music is unique. I am constantly encouraging my students to listen to concert music because if they are trying to find their own voice, they won’t find it by only listening to film music. John Williams doesn’t sound like a second-rate version of anybody. Film composers who are my greatest influence, Jerry Goldsmith, David Raksin who I studied with, Eric Wolfgang Korngold, Max Steiner, Leonard Rosenman the complexity of his music blows my mind, Franz Waxman, I adored his stuff, the older school is the general rule, the ones that were around when I fell in love with music.

Those are the scores that I grew up with. I get it you know, if I was in my twenties right now, I’d be talking about the current generation of composers as being the ones that I fell in love with. The thing that concerns me about younger composers, whereas when I came out in the 80’s all the composers that were my age, we would talk about composers who had been writing in the 30’s and were aware of what Max Steiner did, we were aware of what Eric Wolfgang Korngold had done, we were aware of all that which had preceded us. It seems to me that younger composers think that film music started with Star Wars and that everything before Star Wars unless it was John Williams doesn’t really exist. They think film music started there and that the only film music is from that moment on. I think it’s an unfortunate thing. I think it’s important to have a full understanding of what happened with film music dating way back to its inception, which isn’t that far back anyway. American film music blossomed in the 30’s.

You have worked on a few movies that contain jazz scores, RUM DIARIES, THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO LITTLE etc, is it a more difficult style of music to write or maybe easier?

I’m going to say it’s a little bit easier. Only because being an ex-drummer, generally jazz scores are held together by that swinging drum groove. I always imagine myself behind the set. I grew up playing with avant-garde jazz groups so it’s a language that is in me. Not that orchestra music isn’t, but when you play it, it’s a little different than writing orchestra music. It’s a general rule that it’s a smaller group, so you have less instruments to worry about. It’s basically drums, bass, keyboards and guitars taking care of the harmonies, brass and the tune. The division of labor is a lot easier and it’s not as complex as orchestra music. You aren’t worrying about as many instruments and the lines aren’t as complexly conceived in jazz scores as they are in orchestra scores. At least for the ones I worked on. When I’m doing horror films the intricacies of the lines are really detailed, but when I’m doing jazz scores, I’m just selling a tune. Swinging away and selling a tune.

DRAG ME TO HELL is another powerhouse of a score, with its driving brass and percussion and such inventive use of choir and voices, it just does not relent, the violin solo’s on the score are particularly prominent and at times bring a welcome respite so we can get our breath, who was the soloist for the score?

The violin solo was played by the fantastic violinist Mark Robertson who I had known for years. Though the score was recorded in Bratislava, all the solos were recorded at my studio. Yes, to me that is one of my more exciting scores, only because I got a chance to once again revisit the idea of writing music inspired by the devil. In one hand I am embarrassed and feel somewhat guilty that I’ve worked on more films that deal with the devil than any other composer in Hollywood. This one was exciting because again it gave me the opportunity to feature the violin which is historically an instrument that has been associated with the devil since the beginning of time. During the film I sold this idea to the director Sam Raimi, to imagine that the devil had ten fingers on the violin playing multiple notes at the same time while his tale acted as the bow. He could do things that no other violinist could do. I multi tracked the violin which gave the score this sound. That concept I later expanded upon when I did a concert suite for that score. It’s a 16-minute suite that features the violin. In that instance the violin does things that no soloist could play. It is meant as an audio experience. That was the fun part, having the violin, always acting as the solo voice. The Pied Piper of that score so to speak, because the score was so crazy it allowed the whole score to take a tongue in cheek approach to horror writing and because the film again is over the top, so could the music be. It was like the organ with full stops out all the time being able to do strange and bizarre things orchestrally that I wouldn’t be able to do with any other movie. There were parts of the score that I recall were me breathing or growling loudly, so that was kind of fun.

In your early days of scoring you did work on some movies that were not Oscar material shall we say; do you think a good score can in anyway make a bad movie better?

As they say a good score can dress up a corpse nicely but can never bring it back to life. No, I don’t think a bad film can ever be saved by a score. However, there have been wonderful scores written for films that have certainly not done well. I remember reading a collection of short proverbs or observations by the Japanese contemporary classical composer Toru Takemitzu called Confronting Silences, in which he says no good film music can be written for a bad movie. I remember reading that passage and thinking to myself, sorry Toru as much as I like your music, I have to disagree with you on this one. I put the book down and said I’ve had enough of this. I’d like to be able to disagree with him entirely. If I agreed with him, I’d have to dispose of a lot of my scores. The fact of the matter is that a lot of the movies I have written music for had great acting, great directing, but for whatever reason didn’t work out. In many ways my career has been plagued by many films with great actors that did not achieve success. I always try and carry on with it as though it was Gone with the Wind, as David Raksin said to my UCLA class. I always try to make the music make the movie better. Whenever I am working on a movie, I do believe in it, and never want to believe it’s not going to do well. I don’t know how to pick which films are going to be hits, and which ones are going to misses. As a matter of fact, when I was working on Hellraiser I didn’t think it was going to become a cult classic, neither did Clive! But it did. There are certain films you think are going to do really well and they just bomb. I didn’t think the Grudge was going to be a big hit, but it was super successful! I didn’t think Species was going to be a hit, but what do I know. I don’t know how to pick the winners. I don’t have to force that, it comes naturally. I don’t want anyone to bad mouth the movie when I’m on the movie.

Has any score that I’ve ever written saved a movie? Like I said in my early days when I was hired by these low budget companies, I would create the illusion that the film was going to be bigger than it was.

I would not say you have been typecast as a horror score composer, but do you ever get offered a movie and think “Not another horror”?

I have to start off by saying that there’s nothing worse than someone complaining about being typecast. That’s a common practice here in Los Angeles. Everyone has dreams of getting connected or being understood to be of a certain type and then they come up differently and that’s what they get known for. In my case, it’s definitely horror films, or I just simply call them scary movies. When I was younger, I never had in my mind the notion, when I was really young, I never had the notion in my mind that one day I was going to be best known for writing scary music. I mean, what kid thinks about that? You know?

But as it turns out that seems to be my strength. Yes, I would say that as I’ve gotten older, it’s becoming more and more problematic in being known primarily for horror films or scary films. because there is so much more that I want to do or have done that I wish had gotten more recognition. As much as I love writing music for scary movies, horror films, sci-fi films, thrillers, what not. Genre movies. And there’s certain things you can do in those films you can’t do in any other type of movie. I cannot lie, there is something about having the opportunity to write a killer tune, melody, that I adore. And that doesn’t, the opportunities to write a melody that’s going to have an everlasting pop potential in a horror film is not very likely. Motives [It sounds like CY is saying motives; I’m not sure if it’s motive or motif.] yes. You know the jaws motive? We’ll never forget that.

You know, the shrieking strings from psycho. We’ll never forget those. You know, the piano figure from Halloween. We’ll probably never forget that. But those are motives. They’re not really themes that you carry around with you that will induce fear. So yes. As my career kind of is coming to a conclusion, I have been looking back on what it is I’ve done. More importantly, what it is that I didn’t do and I sure wish that one of the dramas I worked on had really taken flight because if one had, my suspicion is that I would be doing, I would have done less scary movies than I ended up doing. The calls for them were consistent. They came. The calls for dramas, comedies, action films, even science fiction films, were not as frequent. You know, at the end of the day, what you need to do is get connected to a blockbuster film in any genre and you will be able to ride the wave for a while. it just so happens that of all the different types of films that I’ve had the great opportunity to work on, it is the scary films which have done the best in the box office. And at the end of the day, the only film that I’ve really done that’s become a cult classic or a classic of sorts, albeit and cult classic, is Hellraiser. And I’ve often thought that when I’m trying to get a drama, for instance, ultimately when the director looks at my credits and sees that I scored Hellraiser, they’re going to go, “I can’t hire the guy that did Hellraiser. Not for my poignant, deep and moving drama. You know?”

That’d be crazy. I joke with my agent about changing my name. Actually, my name was changed. It used to be Chris Young. And it was my first real agent that during my first meeting told me I had to change my name from Chris to Christopher. And that was because it would induce a certain classiness to me. Like Christopher Palmer or Christopher Walken. And he said, “By the way, it will take up more space on the poster.” You know? Great. So, we changed my name. But I think if I was to change it yet again to something like Cristobel Yunglen, that people might take me more seriously as a drama composer. Because it’s got that sort of artistic ring to it. I joke with the great film composer and my buddy, John Debney, “You know, John, we got to change our names, man. You should be Johannes DeBenay. I’ll be Cristobel or Cristobel Youngelin and you be Johannes DeBenay. (laughs) And then we’ll be considered artists.” But yeah. I’m joking about this but indeed the fact that I have invested so much of my creative time working on movies with the intention to scare people first and foremost is haunting me. And will probably haunt me to the day I split this planet.

I really don’t want to have “The Guy Who Wrote Hellraiser” on my gravestone. However, I’m going to finish off by saying when I get these movies, I set out to do them better than I ever have. I try to find a challenge that makes me feel the need to outdo myself. I never try to schlock it off. Those around me will say, “Chris, you got another horror film? Oh, this should be easy for you.” It never is. I don’t care. When you’re starting a movie, it’s as if you’ve never done one before and you are starting anew. Which is one other point I want to make. I remember reading an interview by Orson Wells in which he said something to the effect of, “A career is made more so by the films that you turn down rather than the films that you take on.” I guess what he meant was, “Beware. If you start accepting movies just for the sake of keeping yourself working, if it turns out you’ve collected a mass of less, undistinguished titles, it’s ultimately going to do more harm to your career than if you sat it out and waited for the good ones.

THE EMPTY MAN is soon to be released can you tell us anything about the movie and score?

This exactly the kind of scary movie that I like the most, or nearly the most, I should say. I cannot tell a lie. My favorite kind of scary movies are ghost stories. A classic ghost story done well on the screen knocks me out. Why? Because the thing that scares us is invisible. We do not see it. We have to use our imagination and internally create the environments that cause us to be frightened. My favorite film being “The Haunting,” the original 1964 version of “The Haunting of Hill House based on the Shirley Jackson book, “The Haunting of Hill House” directed by Robert Wise. That is my absolute favorite scary, scary movie. It’s a ghost story. But next to that, my second favorite type of movie is ones in which someone loses their identity. They go through a set of experiences in which their understanding of themselves is completely destroyed. I don’t know exactly what you call this genre but films like “Angel Heart” or “Jacob’s Ladder” come to mind when I’m talking about this sort of movie. “The Empty Man” sort of falls into that domain. It’s a story of a detective. A policeman who is set off to try to find the daughter of a woman with whom he had an affair with. In the process of trying to locate this woman, he comes across this cult that the daughter is involved with and, in digging deeper into this cult, discovers things about himself that horrify him. The truth of who he really is. I think there’s nothing more horrifying than discovering that everything that you thought you knew about yourself means nothing anymore. That you are not who you think you are. Looking into the mirror and not knowing what you’re looking at anymore. So, it’s a great, great movie. I’m so thrilled to have been a part of it. Directed by David Prior.

This is his first feature. I came onboard because he said that he knew that when he did his first feature, he had to have me come onboard. And we met at a signing. I did a signing at Dark Delicacies, the fantasy, horror, sci-fi bookstore in Burbank a few years ago. He reminded me that’s where he met me and he told me, “You know, when I do my first feature, I want you to score it.” I went, “Sure, you bet.” But then here it was, it happened. The score is one that I’m very proud of because it utilizes field recordings that were created from sounds that we captured around town, and then brought back to the studio to manipulate. Musique concrete style. I’d like to think the sonorities are special, and that it is a continuation of this electronic self that has started to emerge since “Sinister.” It’s taking that to another level.

You released a lot of your soundtracks on promo discs, HUSH, BANDITS etc, do you own the rights to your scores or are they mainly retained by the production companies?

They’re always retained by the production companies. The rights are always retained. The publishing rights. The copyright ownership of the scores are always maintained by the studios that I work for. The only exception being is when I work on a movie where they have so little money that they’re willing to give me part or the entire copyright or publishing rights on the score to compensate for the fact they have no money to pay me or very little as a fee. That’s standard procedure. So what that means is I have really no say over whether or not the score is going to be released on CD. In those instances, apparently there wasn’t enough interest to have them released at the time. Maybe because of the union restrictions on it so rather I did these promotional ones. Promotional ones meaning I’m not asking for any money for them. I’m giving them out as gifts. Just so I can preserve the score, number one and number two, use them to maybe help me get another job. That’s why you see promotional CDs put out by composers. I wish they would come out formally. Which ones? Hush came out officially. It came out as a promo and then ultimately was released officially.

The other one was Bandits. [CY looking at his CDs] Yeah. Bandits was a promotional one. Yeah. I should add to that another reason why score CDs don’t come out is the studio decides they want to release a song CD. Rock song CD and often what happens is they don’t want any competitive CD to come out at the same time, meaning a score CD. So, the people would get confused. They’re there to sell the song CD not the score CD. So that’s also a reason why they don’t come out. That was the case in Bandits. I think there was a rock CD that came out and maybe I had one track on that. Sometimes that’s what happens if they’re putting out a rock CD then yeah you get one track. That’s what happened on that one. What I was given was one track on the pop CD. That’s often what happens is they’ll give you one track.

How many times do you like to watch a movie before you begin to get any fixed ideas about the style of music or indeed where music should be placed to best serve the film?

Where the music is placed is decided by the director, the editor, the picture editor, the music editor and anyone else who has an opinion. So even before I start writing, that’s already decided. Before I go in for the spotting session, I will watch the film a few times so that I have a concept of where the music should go before, I go in there. I have to have an idea of what the music could contribute. That’s number one. Once I get that determined in my mind, what’s the point of view of the music? What can it offer? Then it will help shape where I want to place the music. If I have no idea, no concept of what I think the music can bring to the picture to enhance it, cause it’s like an actor that sings that doesn’t talk, you know? I mean, in notes. If I don’t have that image in my head, then I’m lost so I get that in advance and then go in and s pot the movie. I always try to see the film first without temp music as I think I mentioned in one of the earlier questions. But if that doesn’t happen, then I’ll watch the film with temp at the screening. They usually run the film in a room for me to see with the temp or maybe, if not that, they send me home with a copy with temp, but I also ask for one without temp. So, before I go to the spotting session, I will watch it a few times for the purpose of deciding what the music can be and I will hear where they’ve put the temp and decide whether I think that’s appropriate or not. After we spot the film, I then will watch the film one more time knowing where we’re spotting the film and then I don’t watch it for about ten days. And then, you know, depending on how much time I’ve got on the movie, I’ll walk around with the essence of the movie in my head and the images and the general emotional response that I have from the film and see what comes into my head in terms of music. And then I will record these ideas into my cell phone. Anything that comes in my mind I will record it in my cell phone. Before, my cell phone was a cassette machine or was the digital/audio cassette machine. Then before that it was the actual cassette machine. And that’s always been by my side. Then after a certain period of time, I tabulate the themes, go through them and determine which ones are winners and which ones are losers, what areas of the movie or what thematic categories they might satisfy, kind of knowing in advance the different kinds of themes I think the film will need. How many primary themes. So, at this part of the process, I’m there to try to identify the sonority of the score. Is it electronic? Is it acoustic? Is it a combination of both? What are the kinds of sounds? What are the instruments? And what are the themes? And what and how many different themes am I going to need for the picture? That’s it.

Nowadays, a composer very rarely gets a script to look at because of all the changes and edits that many movies go through, but when you first started out were you sent scripts rather than waiting to go to see a movie and did having the script enable you to maybe prepare more for the assignment?

Well, I’ll tell you that I always get a script before I go for an interview. I think every composer gets a script before they go in for the interview. Even if it’s changing. Just so that when they meet the director and go in for that interview, at least they know the storyline. They’ve read the screenplay. They can start to think about what the music needs to deal with. And they can have an intelligent conversation with it. So, I can’t remember a single interview that I’ve gone on where I haven’t read the script. If I know I’m competing with a bunch of people, if they’re also interviewing other composers. If the directors predetermine that I’m the only guy. The one and only guy then maybe we’ll skip the script. But the purpose of the script is to prepare me for the interview. After the interview is completed, I never use the screenplay to guide me in coming up with tunes. It’s invariable that when I read the script, things will come into my head. I will record them for sure. But knowing that they absolutely mean nothing, probably, because when I see the film, it’s in all likelihood going to be a lot dissimilar from what I think it’s going to look like based on the script and it’s what you see ultimately that generates the ideas that make a difference. So once I see the picture, the script is put to the side. And all the musical ideas that I got when I was reading it. I’ve never once used a single idea that I’ve come up with during the screenplay reading part of the process.

You have collaborated with Director Jon Amiel, a number of times does he has specific requests when you are working on his movies, or is he happy to let you get on with the job as it were?

Yes, I’ve worked with John Amiel more than I’ve worked with any other director. Probably next in line would be Sam Raimi. Sam Raimi as a director and as a producer and I’ve probably done as many movies as I have done with John as director. John is extremely musical. He actually studied the sitar when he was younger and may have had a career being perhaps the preeminent English sitar player but he thought that was a ludicrous idea because the sitar is never going to be played as well by an Englishman as it would be by an Indian so he gave that up. He knows music and I remember the very first movie we worked on, Copycat. I was not the first composer on that movie. That composer had to leave so I came in. Thank the lord he left because I came in and John had these ideas about what the music could be and when we spotted that movie, I remember him being so descriptive, he would talk about high and low and midrange. He would talk about registers as I recall and we also talked about the essential sonority of that group, but I always thought when he was telling me it was like he was hearing the score in his head. And it was a matter of me capturing his actual thoughts. And I think that’s why it worked. Because the way he described what he was looking for, because he was a musician he didn’t say, “You must have a c major chord here or a c minor chord or whatever you do don’t use French horns here because that would be wrong.” He left it open. He wasn’t that specific. But yet the words that he would use to describe the music in semi-musical terms along with the normal dramatic terminology to use to help director/composer were such that I could almost hear what he was thinking so that when we ultimately recorded the score, I think that’s probably what impressed him the most.

He said to me at one point, “You know, this is exactly the score that I imagined in my head would be the right way to go for this movie.” And so, I think a bond was created because I was able to kind of read his mind and so that was the thing that kept us together is that he knew I was always trying to mind meld with him, knowing that he was a musician. He also composed. He was a composer, too. He wrote music, dramatic music for some plays and he had a terrible experience and he decided this is not for me. So, he was a Sitar player turned composer who wrote music to underscore some play production he was a part of and that was a bad experience, so he got out of it. He got into directing. So yes, he always knew what he wanted. And he directed me in the best of ways. It’s a tough thing directing a composer because music is a language that most directors can’t speak. They don’t study music when they’re in school learning how to make a movie. They can speak in every other language, but that’s the one they can’t so they have to figure out a way to use words only to communicate what it is that they’re trying to achieve musically. Again, we have this issue with the temp and that was something that I didn’t experience when I first started. When I first started, every director had to find something that they could say that would communicate what they were looking for without having to refer to a temp. Not many films at the very beginning had temp music. They would talk conceptually. They might say, “Hey, we’d love the score to sound like Psycho. Psycho. That’d be a great thing.” But that’s as far as they would get. You wouldn’t see a scene with a piece of music temped up against it. Problem is with temp music of course is if they get accustomed to it, then when they’re talking about the scene, they talk about the temp music and how the temp, what they like about it and what they don’t like about it. So, when you’re spotting a movie with temp with a director who is not that comfortable to begin with talking about music, it can just degenerate into “I like this. I don’t really like that. What’s that high thing there? No. But the low thing I like. Next.” You know? It gets really kind of crude. So with John, it never got that way. John was always very precise, and I think thrilled when we’d get on the stage and he’d hear the scores because he, interestingly, was a director who never wanted me to mock the scores up. Even when synths became a way. I was a latecomer on that to get into the mocking the scores up because back in the early days if we wanted to present a score to a director, we had to sit at the piano and play it for them. We didn’t hear it except in our heads as composers. The first time we actually heard it was on the stage. John never wanted me to mock things up. He preferred me playing it at the piano, even though I was a terrible pianist. So better you know, I had to describe what it was and he could imagine it. He would use his imagination to hear the orchestra in his head. And so we’d get on the stage and invariably he’d say, “This is what I thought it was going to sound like.” And, “This is exactly the way I thought this cue would work.” Or, “We need to change this.” But he came in with a strong aural picture of what the score was going to sound like, so it didn’t shock him.

Your score for SPIDERMAN 3 is awesome, a soundtrack release was announced but never appeared, do you think this will ever be released?

No. I do not think it will ever be released unless one important thing happens, which is Danny Elfman has to green light it. I should say… No, I do not think it’s going to come out.

The reason why it didn’t come out originally was two-fold. One, the studio had released or was about to release a song CD, which apparently ultimately did not do very well, and it soured their eagerness to want to put a score CD out. Firstly, because it would have competed with the song CD and two, just because I think there was a general feeling of unhappiness with the movie before it came out. It’s a why bother attitude. And number two is that Danny Elfman requested at the time that any reference to his themes, his Spiderman Theme and the was it Green Goblin? Yeah.

The Green Goblin theme that I used from the earlier pictures had to be removed from the cues and since it was an understanding from the beginning that I was going to be using his Spiderman theme and his Green Goblin theme, his themes for those two characters by removing them, they made the cues meaningless. It could not work as a CD without including those two themes and he apparently prohibited or was not happy, I don’t know what it was quite frankly. I was just told if the CD’s going to come out, the only way they could come out is if you can figure out a way to remove those themes. And I tried and it didn’t work. As long as that still holds, I guess it will never come out. And the only other thing that could be a problem of course is the union reuse. It was a gigantic orchestra and choir.

You worked on MONKEY KING and MONKEY KING 2, how did you become involved on these pictures and is scoring a film in China very different from working in the States?

I got involved in that in both of those Monkey Kings because of the relationship I have with the absolutely wonderful English fixer, Paul Talkington. He also is someone who’s constantly hunting down films that need scores and he happened upon this movie. I think they called him and asked for information about recording with orchestras outside of China and at that time, he recommended me and apparently the director wanted to have me come onboard anyway and so Paul became the one who made the connection. Without Paul, this never would have happened. So, I’m indebted to him eternally. Those scores were really a great experience for me.

Why? Because the director was wanting me to maintain that sort of old school melodic-based way of thinking about scoring films. In the first film, there’s not a single electronic anything in it. The second film has moments that incorporate electronics with an orchestra, but the electronics are subsidiary. They’re not that important. It was a giant orchestra and whereas in the first film, I got a chance to pre-record Asian specialty instruments here in LA before recording the orchestra overseas, and the second picture, Monkey King 2, instead of doing solo Asian, mostly Japanese, I should say, instruments, instead of doing solo Japanese instruments and some Chinese instruments, Asian instruments, I did consorts of them. In other words, instead of having one Shamisen, I had a consort of Shamisen’s. Instead of one Koto, I had a consort of Kotos to get a big sound. So that was the main change between the two orchestras. The main difference in scoring with a Chinese director on a Chinese movie is that, whereas in the United States, on a fantasy film, an action film or a horror film, you’re constantly being made aware of moments in a scene, be they cuts or special dramatic moments that the director wants you to acknowledge, to hit. In China, the director Cheang Pou-soi, didn’t care about me hitting many things.